There are worlds of money wasted, at this time of year, and getting things that nobody wants, and nobody cares for after they are got. - Harriet Beecher Stowe, 1850

Happy holidays, everyone! Here we are, madly wrapping gifts as we prepare to wrap up 2024.

At the Johnston household, I sorta phoned it in this year. I decided not to hang the Charlie Brown-style house lights. I’ve been up in the attic a grand total of two times so far this season. When I’m in full Christmas mode, it’s more like two times a DAY. I completely blew off setting up a tree, which saved me at least ten trips right there.

Some of you might be feeling a little judge-y reading that. Totally get it. Kinda comes off as lazy on my part.

I’ll own that.

Just to be clear: I’m not anti-Christmas. It’s just the effort required for something that I’m not especially interested in that turns me off. I freely admit that I love enjoying other people’s decorations, especially when I don’t have to lift a finger.

I think it’s the decoration flexing that turns me off. There’s a fine line between participating in a little friendly neighborhood decoration competition, and blowing out transformers because you National Lampooned your house to one-up the folks across the street who went all in on inflatables.

However, the history of the Christmas holiday is another topic entirely that I am delighted to explore with all that effort I saved not putting up lights or a tree. As luck would have it, a very interesting book on this topic found its way into my hands recently. It’s full of all sorts of fascinating tidbits that I thought you might enjoy as you gather round your cozy fireplace with a hot toddy, Johnny Mathis Christmas music on in the background.

Like that Amazon food gift basket we’re all sending to each other, The Battle For Christmas by Stephen Nissenbaum is overflowing with a satisfying variety of delectable tidbits.

Celebrating Christmas as we know it, full-on capitalist consumer mode, has only been going on for a couple of hundred years. In fact, after the Puritans landed in New England, most people didn’t even celebrate Christmas. It was actually illegal in Massachusetts from 1659-1681.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. It’s quite a leap from a holiday not really being your cup of tea to it actually being outlawed. There are a couple of reasons for this. One is that Christmas just was not that big of a deal back then, specifically with the early settlers of New England, many of whom were Puritans. It was the 17th century version of National Bosses Day. Popular with bosses, but no one else gives a fig. For one thing, they had a beef with the Catholic Church for designating what the Puritans considered a completely random day as the birth of Jesus.

Also in those days, the Christmas season was known more for its chaotic revelry than genteel gift-giving. Think Mardi Gras, but with wassail. After the fall harvest and with the onset of chilly winter weather, farm activities ground to a halt. There was only so much thumb-twiddling the lower classes could stand. So when the winter solstice hybrid celebration offered an opportunity/excuse to let your hair down and go a little wild, many folks were totally on board.

Those early “Christmas” celebrations went something like this: the working folk, usually young men, went knocking on the doors of the quality, demanding snacks and booze. Initially this was intended as a reward, perhaps for a little festive singing. Sometimes they wore masks or other bizarre attire, partly because it was fun and partly because they were about to get rowdy and didn’t want to be recognized.

It was considered poor form for the quality not to offer the miscreants snacks and drinks when they came knocking. And those drinks better have booze in them! They complied out of fear of retribution. Vandalism was common. I believe ‘extortion’ is the word we’re looking for here.

There was no specific date for the “Christmas” shenanigans. Sometimes it was a single evening. Other places, it dragged on for days or even weeks.

You can probably see why some folks were not exactly enthralled with encouraging this activity. Especially when they had other challenges, like forming a new colony across the ocean. So when they arrived in New England, the Puritans didn’t bother bringing any of those pesky Christmas traditions with them. They cleaned holiday house.

In the early 1800s, a combination of factors steered Christmas in a new direction. Some of the upper crust in the New England area, especially New York City, had their fill of the wilding that persisted among the lower classes this time of year.

A New York City resident (and fellow history nerd) by the name of John Pintard became obsessed with the idea of upgrading Christmas after experiencing first-hand some annoying antics outside his upscale home near Wall Street in Manhattan. They soured him on the carousing tradition that had survived the crossing with the early New England settlers. In author Nissenbaum’s words, “Since there existed no Christmas rituals that were socially acceptable to the upper class, Pintard took on the responsibility of inventing them.”

Pintard experimented with a variety of strategies. Moving the celebration indoors, for one thing. A quiet evening at home, pondering the meaning of life. Visiting friends, but in a civilized fashion.

Some of the religions were on board. Celebrate indoors, you say? Like, inside a church? We’re in.

The logic was, by making it more of a cozy family affair, or more affiliated with religious service than a kegger, that would help tamp down the unseemly behaviors this holiday had become known for.

Okay, progress. But we’re not quite there yet.

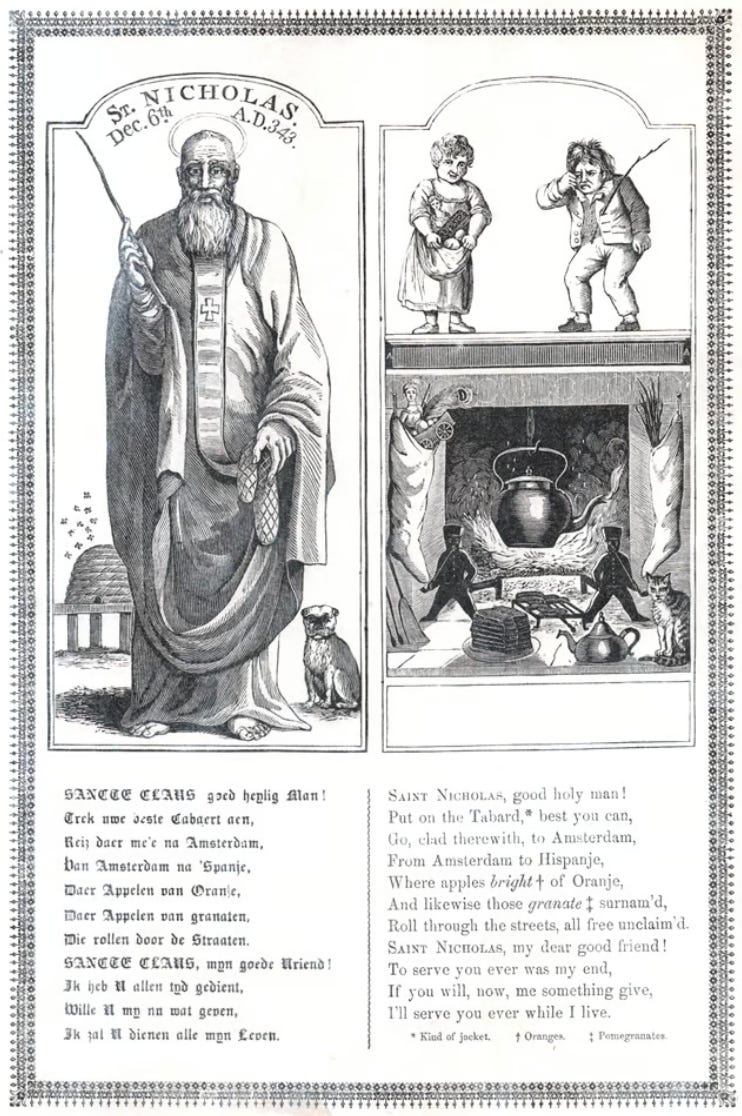

When Pintard stumbled on the history of St. Nicholas as the patron saint of New Amsterdam, now known as his home city of NYC, something clicked. Pintard commissioned a broadside of St. Nicholas featuring the saintly figure rewarding a young girl with snacks for being good during the year, and caning a young boy who was not.

Ouch. I’ll take the lump of coal instead, sir.

This illustration appeared at the New York Historical Society’s St. Nicholas Festival dinner (held on December 6, St. Nick’s Saint Day) in 1810.

The broadside had a sort of butterfly effect in that one of the people who saw it was a fellow upper crust resident of NYC. You may have heard of him. Clement Clarke Moore. Yes, THAT Clement Moore.

Inspiration struck. Moore’s iconic poem was initially published in 1822. It’s hard to quantify the impact this story has had on our culture, but I’ll give it a go. Seismic? Meteoric? Revolutionary? Without Moore, who was partially inspired by Pintard, December 25 might still just be another minor religious saint’s day.

Compared to the lengthy transition from Puritan ban to the resurrection of a New Amsterdam tradition, it didn’t take long for the newly rebranded St. Nick/Santa Claus to take hold. By the mid-1800s, as you can see from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s quote at the top of this post, the holiday had been completely commercialized, morphing from young men wilding through the English countryside into the consumer frenzy we are familiar with today. The wassailers of old are now the Wal-Mart shoppers on Black Friday, still willing to break down doors and bust a few heads if that’s what it takes to get their holiday score.

I am tempted to go on, filling you in on how the tradition of the Christmas tree fits into the picture, and the shift from food/drink to actual presents, and how a sorta stuffy-looking saint transformed into a ‘jolly old elf’, and how Christmas evolved from physical excess to financial excess. But I think I will save that for a future post. This one is already a little too long, and those presents I have stashed away won’t wrap themselves.

Merry Christmas to all, and to all a good night!

I will leave you with three things.

Contrary opinions about Christmas have filtered down from those early Puritans to the present day. This vicar’s recent reality check for some local school children went over like a lead balloon.

I recently gave Snoop Dogg’s cookie recipe a try (even though I’m not a peanut butter fan). They’re awesome!

My writer buddy Rob Espenscheid has a new book coming out next spring, The Rise of the Mad March. It’s the story of a fictional punk band in the 1970s. You can pre-order it here on Amazon.

My latest book, Double Fault, is available now on Amazon.

When an investigation of illegal match fixing by the Russian mob brings the FBI to her tennis club in the person of hunky agent Wilson DuBois, Veronica Burk vows to help him solve the case quickly before her own very successful gambling habit falls under suspicion.

My historical fiction book, Ventured, is also available now on Amazon.

When she takes a chance on making a new life for herself, French orphan and cutpurse extraordinaire Belle must find a way to survive in the New World—or she may not live long enough to enjoy it.

My YA trilogy is also still available if historical fiction isn’t your thing.

Brody Morgan grew up starring in commercials for his dad's mega food corporation. What will Brody do when he discovers what he's really been selling?

So interesting to learn how Christmas festivities came to North America. Thanks for sharing your research on this, Lissa, and I like how you’re keeping it low-key this year. All the best to you and yours!

Two things. Obviously, thanks for plugging The Rise of the Mad March. Every link helps. You've 2 million subscribers, right? Just kidding. Knowing you, that's a low figure. Re: xmas. Most every year in December I watch: The Man Who Invented Christmas, starring Dan Stevens and Christopher Plummer. A British film detailing how Charles Dickens wrote The Christmas Carol. The movie is full of serendipity: Dickens struggling with his manuscript – has a meal at an inn with a grizzled waiter named Marley. You get the point. Another point being that the Dickens novella was published around 12/20 1843 and was an astonishing success abetting the xmas celebration we have today.